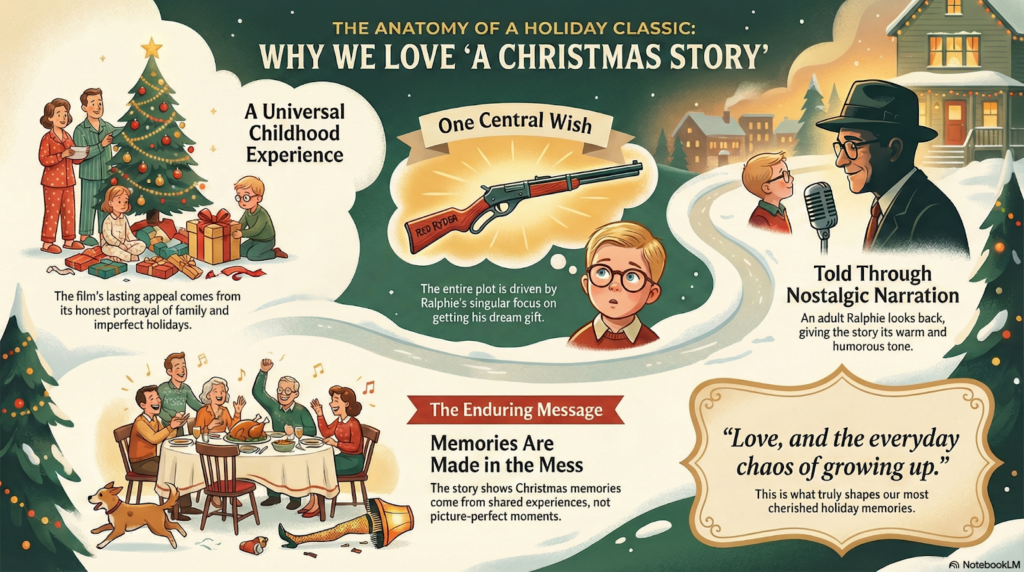

A Christmas Story stands as one of the most enduring and beloved holiday films in American cinema, capturing the imagination of audiences since its 1983 release. Directed by Bob Clark and narrated by Jean Shepherd, whose semi-autobiographical essays provided the source material, the film tells the story of nine-year-old Ralphie Parker and his single-minded quest to receive an Official Red Ryder Carbine Action Two-Hundred-Shot Range Model Air Rifle for Christmas. Set in the fictional town of Hohman, Indiana during the 1940s, the film transcends its simple plot to become a profound meditation on childhood innocence, family relationships, and the universal experiences that define the American holiday season. What makes A Christmas Story truly special is not just its humor or nostalgic setting, but its ability to capture authentic moments of childhood with honesty, warmth, and remarkable insight into human nature.

The genius of A Christmas Story lies in its structure as a series of interconnected vignettes rather than a traditional linear narrative. Each scene functions as a self-contained memory, much like how we recall our own childhoods in distinct episodes rather than continuous stories. This episodic structure perfectly mirrors how adult Ralphie, voiced by Jean Shepherd himself, remembers that particular Christmas from his youth. The film moves seamlessly from Ralphie’s elaborate daydreams about becoming a hero with his BB gun to the infamous tongue-on-frozen-flagpole incident, from the leg lamp controversy to the pink bunny pajamas humiliation, creating a tapestry of experiences that feel both specific and universal.

The narration by adult Ralphie provides a crucial dual perspective that elevates the film beyond simple comedy. When young Ralphie fantasizes about saving his family from bandits with his BB gun, adult Ralphie’s narration acknowledges the absurdity while also honoring the sincerity of childhood imagination. This technique allows the film to be simultaneously funny and tender, mocking and affectionate, critical and celebratory. The adult narrator understands what his younger self could not, that the adults dismissing his BB gun dreams were motivated by genuine concern, that his parents’ arguments were actually expressions of love, and that the memories of family togetherness matter far more than the gifts themselves.

Central to the film’s enduring appeal is its portrayal of childhood from a child’s perspective rather than an adult’s idealized memory. Ralphie’s world contains real frustrations, genuine fears, and authentic triumphs that resonate with anyone who remembers the intensity of childhood emotions. His terror of the department store Santa, who mechanically processes children with his boot-pushing elf assistants, captures the gap between childhood expectations and disappointing reality. His humiliation when forced to model the pink bunny suit his aunt made reflects the powerlessness children feel when adults make decisions for them. His rage when confronting bully Scut Farkus and beating him into submission acknowledges the violence lurking beneath childhood innocence that adults prefer to ignore.

The film treats these moments with complete seriousness from Ralphie’s perspective even while inviting adult audiences to see the humor. When Ralphie accidentally says “fudge” except he doesn’t say fudge, and his mother washes his mouth with soap, the scene works on multiple levels. For Ralphie, it represents betrayal and injustice since he learned the word from his father. For adults, it highlights parenting hypocrisies and the arbitrary nature of rules that make sense to enforcers but not to those being disciplined. The soap punishment becomes a rite of passage, a quintessentially American childhood experience that bridges generations.

The family dynamics in A Christmas Story provide much of the film’s depth and relatability. The Parker family represents a typical middle-class American household of the 1940s, struggling with economic limitations while maintaining pride and optimism. The father, called only “The Old Man” in the narration, embodies working-class aspirations and frustrations. His delight in winning the infamous leg lamp, which he genuinely believes is a high-class piece of art, reveals both his yearning for status and his lack of sophistication. His battles with the malfunctioning furnace, which he calls a variety of creative profanities, show a man fighting against circumstances beyond his control with only his wit and stubbornness as weapons.

Mother, played with perfect warmth by Melinda Dillon, represents patience, practicality, and quiet strength. She manages household chaos with competent grace, mediates conflicts, protects her children from excessive discipline, and somehow maintains order in a house dominated by male energy and dysfunction. Her “accidental” breaking of the leg lamp demonstrates her subtle power within the family structure, exercising agency through apparent accidents rather than direct confrontation. The scene where she creates a story to protect Ralphie from punishment for saying the forbidden word shows maternal love manifesting as strategic dishonesty, a complex moral territory the film explores without judgment.

The relationship between Ralphie and his younger brother Randy adds another layer of authentic childhood portrayal. Randy, who refuses to eat, hides under the sink during conflicts, and wears so many winter clothes he cannot lower his arms, represents childhood at its most vulnerable and absurd. Ralphie’s mixture of protective affection and annoyed superiority toward Randy captures sibling dynamics perfectly. The Christmas morning scene where Randy, buried in wrapping paper like a mummy, “looks like a pink nightmare” showcases the chaos and joy of childhood holidays without sentimentality or false perfection.

The theme of coming of age runs throughout A Christmas Story as Ralphie navigates the transition from childhood dependence on his mother to identification with his father. The BB gun itself symbolizes this maturation, representing danger, responsibility, and traditionally masculine pursuits that mothers fear and fathers eventually encourage. When his father gives him the gun after his mother has repeatedly refused, it marks a shift in allegiance and understanding. The father recognizes something in Ralphie that the mother either cannot or will not see, that the boy is ready for certain risks and responsibilities that come with growing up.

The film’s treatment of adult authority figures reveals the child’s eye view of a world run by arbitrary and sometimes incomprehensible rules. Miss Shields, Ralphie’s teacher, assigns an essay about what students want for Christmas but responds to Ralphie’s passionate composition about the BB gun with a grade of C+ and a dismissive “you’ll shoot your eye out” comment. Santa Claus, rather than a magical gift-giver, appears as a tired, mechanical worker who rushes children through a production line and literally kicks them down a slide when their time ends. These portrayals demystify adult authority while acknowledging that children must navigate systems they neither control nor fully understand.

The famous triple dog dare scene, where Flick sticks his tongue to a frozen flagpole, has become iconic precisely because it captures childhood logic and peer pressure dynamics with uncomfortable accuracy. The escalation from dare to double dare to double dog dare to the ultimate triple dog dare represents childhood’s intricate social hierarchies and unwritten codes. When the school bell rings and all the other children abandon Flick to his frozen fate, prioritizing their own safety over loyalty, the film acknowledges childhood’s capacity for cruelty without condemning it, simply presenting it as truth.

The film’s portrayal of 1940s America, while nostalgic, avoids romanticizing the era. The economic struggles are real, the cold is genuinely uncomfortable, the disappointments are authentic, and the frustrations are palpable. The flat tire on the way home from selecting a Christmas tree, forcing the father and Ralphie to change it in freezing temperatures, represents the everyday difficulties that test family bonds. These moments of adversity, handled with humor and resilience, demonstrate that nostalgia in A Christmas Story is not about wishing for a simpler past but recognizing that all eras have their challenges and joys.

The commercialization of Christmas receives subtle commentary throughout the film. The department store Santa operation, the window displays hypnotizing Ralphie, the decoder pin that ends up being a crummy commercial for Ovaltine, and the father’s obsession with winning prizes all reflect how consumer culture shapes holiday experiences. Yet the film never becomes preachy about materialism. It accepts that gifts matter to children, that parents take pride in providing them, and that the desire for material things coexists with genuine family love without contradiction.

The film’s humor derives from recognition rather than exaggeration. The images of Randy eating like a piglet, the father’s profanity-laced fights with the furnace, the mother’s theatrical reaction to Ralphie’s use of a four-letter word, and the Chinese restaurant workers singing “Deck the Halls” with enthusiasm and creative pronunciation all work because they feel authentic rather than manufactured for laughs. The comedy emerges from character and situation rather than jokes, making the humor timeless and universally relatable rather than dependent on cultural references that date quickly.

A Christmas Story achieves something remarkably difficult in cinema: it captures the texture and feeling of childhood memory rather than just depicting events from childhood. The soft focus of certain scenes, the way some moments expand while others compress, and the intrusion of adult Ralphie’s commentary create the sensation of reminiscence rather than straightforward storytelling. This approach makes the film deeply personal for viewers, triggering their own childhood memories and emotions rather than simply entertaining them with someone else’s story.

The film’s ending perfectly balances satisfaction and realism. Ralphie does receive his coveted BB gun, fulfilling the Christmas wish that drove the narrative, but he immediately shoots himself in the eye with a ricocheting BB, vindicating every adult’s warning while also demonstrating that surviving such mishaps is part of growing up. He quickly concocts a lie about an icicle causing the broken glasses, showing he has learned how to navigate adult expectations. The family’s Christmas dinner disaster, when the neighbor’s dogs destroy the turkey, leads them to a Chinese restaurant for a decidedly non-traditional holiday meal. Yet this seeming catastrophe becomes one of Ralphie’s fondest memories, not despite its imperfection but because of it.

The final image of Ralphie sleeping peacefully with his BB gun demonstrates that getting what you want, while important, matters less than the journey and the memories created along the way. Adult Ralphie’s narration confirms that subsequent Christmases never quite matched that one, not because the gift was so special, but because that Christmas captured something unrepeatable about childhood, family, and the magical ordinariness of growing up in mid-century America.

A Christmas Story became a cultural phenomenon not through immediate box office success but through gradual recognition and the creation of the 24-hour marathon broadcast tradition. The film’s reputation grew through repeated viewings that revealed layers of nuance and authenticity not immediately apparent in first viewing. Its quotability, visual iconography like the leg lamp and pink bunny suit, and universal themes ensure its relevance across generations. The film speaks to the child in every adult while helping children see that their experiences, however mundane they might seem, are worth remembering and celebrating.

The film reminds us that holiday perfection is neither achievable nor particularly desirable. The Parker family’s Christmas contains arguments, disappointments, near disasters, and moments of genuine chaos alongside the joy, love, laughter, and togetherness. This honest portrayal of family life during the holidays resonates more deeply than sanitized versions of perfect celebrations. A Christmas Story tells us that our imperfect holidays, with all their stress and surprises, are what create lasting memories and bind families together. The film celebrates the messy reality of family life rather than an idealized fantasy, making it both more honest and ultimately more comforting than traditional holiday fare.

Conclusion

A Christmas Story endures as a holiday classic because it captures fundamental truths about childhood, family, and American life with humor, honesty, and genuine affection. The film’s power lies not in its plot but in its accumulation of authentic moments that resonate across generations and backgrounds. Through young Ralphie’s quest for a BB gun, we revisit our own childhood desires and the adults who both thwarted and enabled them. Through the Parker family’s imperfect but loving dynamics, we recognize our own families with all their quirks and contradictions. The film reminds us that the holidays are ultimately about creating memories with the people we love, even when, or especially when, nothing goes according to plan. In capturing one boy’s Christmas in 1940s Indiana, A Christmas Story somehow captures everyone’s Christmas everywhere, making it a truly timeless celebration of what it means to be human, to be part of a family, and to remember with fondness the mixture of joy and chaos that defines both childhood and the holiday season.

Belekar Sir is the founder and lead instructor at Belekar Sir’s Academy, a trusted name in English language education. With over a decade of teaching experience, he has helped thousands of students—from beginners to advanced learners—develop fluency, confidence, and real-world communication skills. Known for his practical teaching style and deep understanding of learner needs, Belekar Sir is passionate about making English accessible and empowering for everyone. When he’s not teaching, he’s creating resources and guides to support learners on their journey to mastering spoken English.